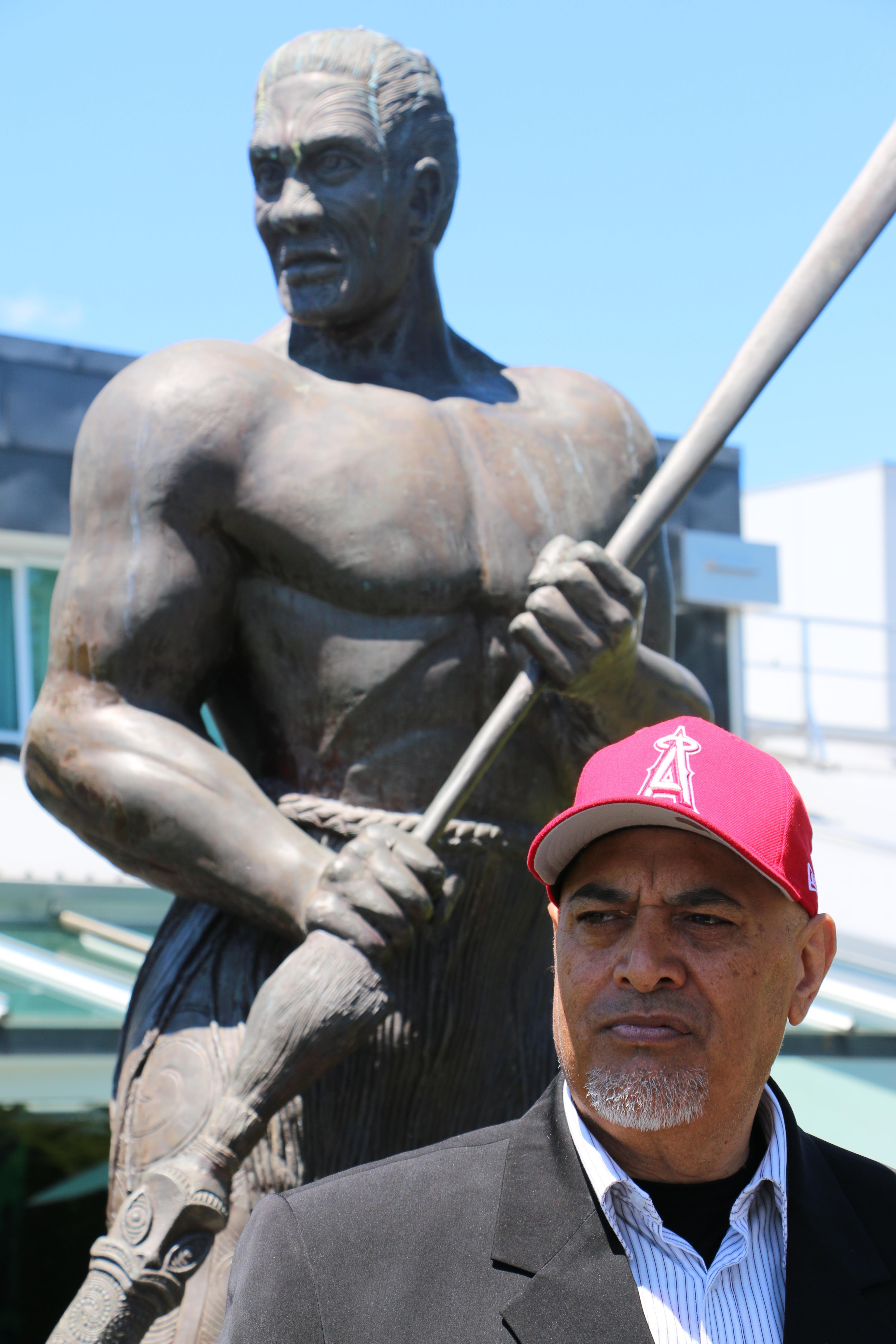

Master of Applied Indigenous Knowledge graduate Hopere Chase.

Hopere Chase credits his 16-year-old moko Anton with being his kaitiaki.

It’s an idea that forms part of his He Waka Hiringa Master of Applied Indigenous Studies research and one he used while completing his Bachelor of Bicultural Social Work degree and “if I do my PhD, I’ll probably use him again,” Hopere, 57, says.

The idea of having his moko as his kaitiaki came about when Hopere first held baby Anton in his arms and realised something was changing in his life and Anton was the catalyst for that change.

“I looked into his face and even though he couldn’t speak, it’s like he was asking me ‘so what are you going to do now’, Hopere says.

“I decided I wanted to set an example to him, which is what I hadn’t done for my kids. I was holding him - wearing my patch - and I looked in the mirror and saw myself and knew something had to change.”

What changed was that Hopere quit the Mongrel Mob – where he’d spent 27 years since joining as a teenager - became a social worker and now - 16 years later - completed his Master of Applied Indigenous Knowledge degree at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.

But leaving the Mongrel Mob, Hopere says, isn’t easy.

“I was struggling to put food on the table. I had to go on the dole.”

The easy option would have been to go back to the gang.

“In the gang, money was never a problem, from the drugs we sold or the burglaries we did.”

But things looked up for Hopere when one of his sisters found him a casual job working in the mental health sector.

“I didn’t want to do it but eventually I had to because we had no money. At first it was just for the money, I didn’t want the job but I had to put food on the table.”

The job involved working with people who had mental health challenges and preparing them to re-enter the community.

“I was helping guys in rehab, getting them out of hospital, which is odd because I’d spent so long putting people in to hospital. Over time I found I had the skills in my kete to do this job. And some of them were asking to work with me because I understood them. Some were going through depression, and prison is a very depressing place so I could understand what they were going through.”

Eventually Hopere was offered a management role but had no formal qualifications.

“The boss said I had the skill and life experience but not the qualification so in 2011 I enrolled in the Bachelor of Bicultural Social Work degree at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.”

It was another big step.

“I sucked at education when I was young,” he says.

It’s not hard to figure out why. Growing up one of 13 children in a home where the sound of the car coming home from the pub signified the start of the next hiding for his mother. No comfort, no security, no support. Something like school held little attraction and he paid little attention.

“There were seven of us. We’d take a small glass jar to school and go down the back of the field and sniff petrol because it made us feel good. We all ended up in gangs and I now know that they had the same sort of childhood that I did. The gangs gave us comfort, security, a home.”

After completing his social work degree it was another big step up to tackle his masters.

“This is the culmination from year one to year two to where I am today,” he says.

“My kaupapa when I came in here was me looking for answers to why gangs behave like they do but through my study it turned on to myself and asked ‘why did I join the gang?’. I was suffering but I didn’t know I was suffering.”

The first part of his masters study was ‘Ko Wai Au’ (Who Am I) and was something Hopere initially struggled with.

“I wouldn’t talk about things that hurt me. My home life, domestic violence, gangs. I didn’t want to revisit that or to talk about it. I thought I was healed from all that but I wasn’t. I had to put all that in and He Waka Hiringa showed me how to go into that and how to come back out of it. It changed my thinking.”

Hopere says it’s unlikely he would have been able to achieve his qualifications anywhere other than Te Wānanga o Aotearoa and says that’s no coincidence.

“We think we came here to learn something but it was our tūpuna who sent us here. So the wānanga has played a key role in my life. It’s made me see the future a lot clearer. The wānanga empowers our people so much. It’s enabled us to be secure, myself and my whānau. I love it.”